Digital versus Electronic Finance

In the 90s, the UN thought a lot about e-commerce and the Internet. Unlike most, they had a place to start from.

(Warning: Hacked together reductionist allegorical history ahead.)

That place was Telex, the successor to the telegram. And Telex is what glued together the corners of global commerce that ran through computers. Electronic instructions in that environment were machine-encoded telegrams shuddering out of dot-matrix printers from private copper wires among 1970s mainframes.

You had some wires of your own, you leased some wires from a network provider, and your counter-party had some wires. And if someone asked your sysadmin which wires were used and who owned them, they would have been able to give them a clear answer.

The Internet was different; the Internet was feral. There was no such answer. Great for cat pictures, not so great for multi-million dollar letters of credit. The Internet made digital signatures based on cryptography relevant in a way it never had in a world where the wires themselves were known and trusted.

So UNCITRAL (the bit of the UN that tries to to suggest laws) drew a line: the old world of trusted telegrams (and faxes and recorded phone deals etc) was to be Electronic; the new world of crypto signature magic was to be Digital.

Which makes reasonable sense. The old Telex networks might have been digital in operation by the 90s, but this was just a way to stop signals degrading on the the wire. Those networks were dependent on electronics existing, but for the most part, you could have done things the same way using analog signals.

Digital signatures are maths. So we need to turn our messages into numbers before we can sign them. They can’t be faxes where the odd letter can smudge without it mattering. And communication networks with unknown routing can’t be implemented reliably with analogue circuits. (That’s why we first build digital networks. Following a nuclear war it was impossible to assume that any individual telephone exchange would survive!)

Messages on the wire are transient, so purely electronic signatures need to be communicated to a trusted third party to be relied on later. Typically this would be the provider of the wires. Something that also mapped nicely onto the emerging web economy, where the trusted party was simply a central website like eBay or DocuSign.

Electronic agreements, in practice, presume central utilities, and implicitly rely on wire-level security. Digital agreements presume secure end-points devices that can sign exactly what their owners intend, and disregard the intermediary infrastructure. This distinction to avoids spurious arguments over how a digital signature has been transmitted, and gives a basis for regulating intermediaries who vouch for electronic signatures.

Think of octopi in mail rooms, eg. they can lose or mishandle your mail, but not sign for you, versus octopuses as scribes, eg, may or may not pass on what you originally said to them. It’s worth noting that dishonest scribes in Egypt were liable to have their hands removed. And, yet given that the law existed, this presumably still happened…

Virtually all our online agreements today live within web platforms, and so are electronic. If eBay shuts down, I can’t use my account. Given that we were running Windows 95 while all this was being built, this is perhaps not a bad thing. Our PC end-points were made of silicon plywood, and eBay can afford a lot more fraud monitoring than I can! Also, a few countries like Estonia aside, we still don’t have the infrastructure required for digital signatures to reliably represent real people.

Of course, it’s agreements we care about, not individual signatures. And agreements can be varied by newly signed instructions at any time. I might sell my house, I might never even have been the legitimate owner. There needs to be some form of memory. And, in everything we’ve described so far, there must be an infrastructure (with an owner) for there to be memory in the system. Even if our octopuses are just manning the mailrooms and the archives, they still need to be there. And with them there, they might as well do the books and hold the money.

We don’t really have digital commerce with eBay, we have electronic commerce. And we don’t have digital finance with an online bank, we have electronic finance. If my central utilities don’t cooperate, I can’t prove much about the relationship myself.

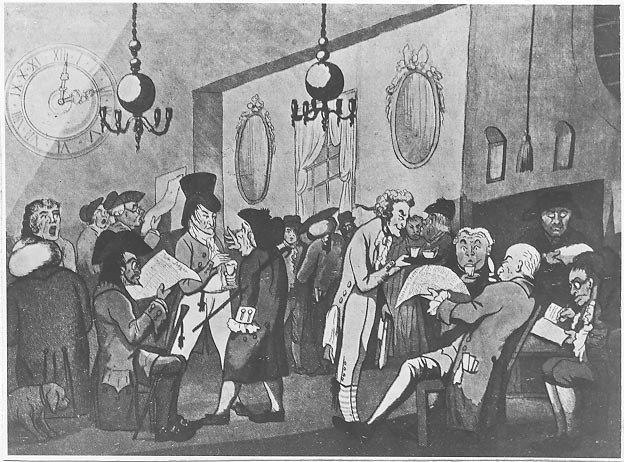

Since electronic memory is socially important, we regulate it. We might not talk about regulating memory per se, but that’s usually the dividing line. No one will get arrested for owning a coffee shop where the patrons mostly trade insurance contracts all day. Start running bookkeeping between them, and someone will want to have a word.

Regulation protects against corruption of that memory, but also broader concerns like fairness and consumer protection. Not to say that this is all bad. We probably are better off because of people like the SEC.

Our current global trading systems are electronic, not digital. Regulation presumes a choke-point for anything that happens through a computer. There must be memory, therefore someone will maintain that memory (plus a whole lot more for convenience), and presumably both promote and profit from it. Find scribe, remove writing hand, problem solved – no more Pirate Bay, no more EtherDelta.

Blockchain broke that limitation on memory, just as digital signatures broke authenticity away from the physical wire. By employing game theory to create cooperative games, memory doesn’t need to reside in a single “master” octopus. It can be an emergent property of a crowd of octopi loyal to many masters (and some perhaps to none).

If I were to write a set of smart contracts to implement binary options based on logic from a finance textbook, then a third person was to pick them up on a test network to run a competitor for students with play money, then a student then rolled on to an investment bank and re-deployed the code to hack together a weather options trading environment, but didn’t give anyone outside the financial world access, etc. A year later, the world has an open market in weather insurance. Who do we blame? If no-one stood to profit, if no-one both created and promoted it? If no-one can feasible switch it off?

Blame could be arbitrarily assigned, but it would not actually bring an end to the activity. Perhaps the weather companies could be persuaded to cut their data feeds, or alter them not to trigger any payouts. Maybe participants could be taxed 100% of their payouts. Perhaps we always blame the party who published the contract to the network, much as Dutch traffic accidents are by law never the fault of a cyclist, only the driver. Or the reverse, if there is no institution, every participant is guilty of conspiring to run an unregulated institution!

Digital memory is here and we need a discussions within the financial and regulatory communities similar those in trade circles when digital signatures and the Internet emerged. That conversation established a new paradigm that adapted all the principles of the old way of doing things, but dealt with the difference in operational mechanics.

The re-conceptualisation of electronic into digital, shifted liability to the end-points, neutered the providers of wires turning them from trusted parties to a mere substrate like the airwaves, and most importantly, created new institutional categories, like certificate authorities, that better defined the narrower roles that remained for them.

We need to go back and look at the pre-electronic world, to remember what made us regulate the corporate octopi in the first place, and how we’re going to deal with a Lloyd’s coffee house of 8 billion people.